Maria Esperanza Diaz Ruiz expected to pay a smuggler to cross the US-Mexico border. Then she learned that a new program from the Biden administration would allow her to walk free as long as she had a tale of woe from home.

She is one of the migrants benefiting from Biden’s new policy, which turns undocumented immigrants into legal “parolees,” giving them work permits and settling in America, according to the Center for Immigration Studies, which has tracked Ms. Díaz Ruiz and others arriving.

“It’s real,” she told the center’s Todd Bensman. “It’s not a trick.”

Her excuse for parole in the US is that she worked for a Nicaraguan government official who was homosexual. Her ex-husband threatened both her and her boss, she told Mr Bensman.

“I had to leave because I was going to be killed,” she said.

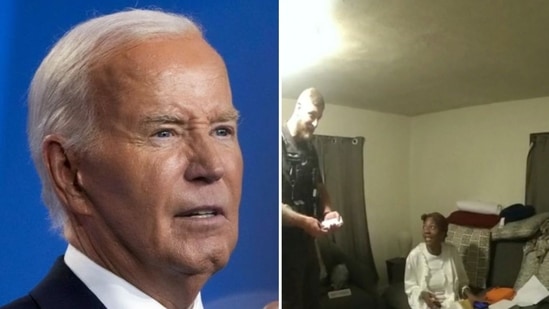

Armed with documents and a criminal background check, she joined a group of about two dozen migrants who were entered into the U.S. Border Patrol system, taken to the border crossing between Mexicali and Calexico, California, and handed over to U.S. authorities.

Mr. Bensman was given unhindered access to the Mexican side of the processing and released his findings on Monday.

He said it’s not just about entry points along the border. Some migrants are flown from Cancun or Monterrey directly to US airports.

“This appears to be part of a deliberate strategy to create workarounds for court-ordered deportation policies, and to reduce the politically painful statistics of illegal crossings by directing more and more people through these legalized crossings,” he said. “Although neither DHS nor the White House has publicized this legalized entry program, DHS Secretary Alejandro Mayorkas has repeatedly communicated it in his oft-stated intentions to create ‘legal pathways’ as part of the administration’s overall vision of a ‘safe, orderly and humane “. for immigration at the southern border.’

The program relies on Mr. Mayorkas’ right to “humanitarian parole.” It can admit people to the US outside the normal temporary or immigrant visa system.

This administration is not the first to rely on parole, but it is the most extensive in its use, having used the authority to bring in evacuees from Afghanistan, Ukrainians seeking to escape war in their country, and hundreds of thousands of migrants from the many countries now appear on the southern border.

Parole grants a one-year permit to stay in the United States. Mr. Mayorkas can extend it, but those on parole can also apply for asylum or try to find another, more permanent legal status.

And even if they don’t, given the limited resources of U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement and Mr. Mayorkas’ orders to limit deportations, there is little chance they will be pushed out at the end of the year.

Some legal experts say parole has been twisted far beyond its purpose, which was to welcome on a case-by-case basis those with an urgent humanitarian need or “significant public benefit.”

Chief Justice John G. Roberts Jr. hinted as much during oral argument earlier this year on the Biden team’s bid to end the Trump-era “Remain in Mexico” policy.

“It comes down to the question of the interpretation of parole provisions and whether, I think, substantial public benefit can be accommodated to — how far you want to stretch it,” he told a government lawyer.

However, during the same argument, Judge Brett M. Kavanagh said the court gave broad discretion to administrations to determine what is in the public interest in parole cases.

Judging by the numbers flowing north, the Biden administration will need that kind of latitude.

The Mexican operation in Mexicali is tripling in size to handle the number of people.

But Mr. Bensman said there was reason to be skeptical about the merits of the cases.

The US wants evidence of hardship at home to back up tales of woe. But it can be created after the fact. He said law professors and university students help migrants make police reports by phone with authorities in their home countries and then use that as evidence for their claims.

One local pastor told Mr. Bensman that law students were training migrants to reinforce their demands.

The pastor said that in Tijuana, west of Mexicali, he had heard that city officials were demanding bribes to include migrants on their lists.

.jpg)