KHERSON, Ukraine (AP) — Dr. Oleg Duda, an oncology surgeon at a hospital in Lviv, Ukraine, was in the middle of a complicated, dangerous operation when he heard explosions nearby. After a few moments the light went out.

Duda had no choice but to continue working with only a headlight for light. The lights came back on when the generator kicked in three minutes later, but it felt like an eternity.

“These fatal moments could have cost the patient his life,” Duda told the Associated Press.

The operation on the main line took place on November 15, when the city in western Ukraine suffered a blackout when Russia fired another missile salvo at Ukraine’s power grid, damaging nearly 50% of the country’s energy facilities.

The devastating strikes, which continued last week and plunged the country back into darkness, have strained and disrupted a health care system already battered by years of corruption, mismanagement, the COVID-19 pandemic and nine months of war.

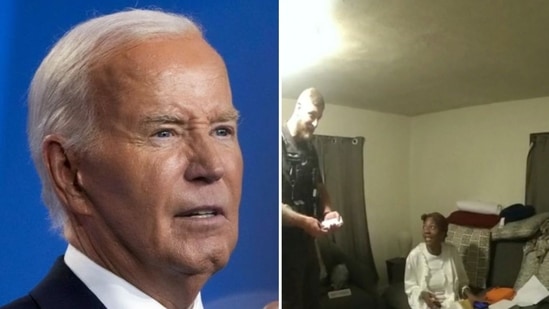

Planned operations are postponed; patient records are unavailable due to an internet outage; and paramedics had to use flashlights to examine patients in dark apartments.

Last week, the World Health Organization said Ukraine’s health care system was facing “the darkest days of the war” amid a growing energy crisis, the onset of a cold winter and other challenges.

“This winter will be dangerous for the lives of millions of people in Ukraine,” the WHO regional director for Europe, Dr. Hans Kluge, said in a statement.

He predicted that 2 to 3 million people could leave their homes in search of warmth and safety and “face unique health challenges, including respiratory infections such as COVID-19, pneumonia and influenza.”

Last week, the Kyiv Heart Institute published a video on its Facebook page in which surgeons operate on a child’s heart using only headlights and a battery-powered flashlight.

“Rejoice, Russians, the child is lying on the table, and during the operation the light completely went out,” said the director of the capital institute, Dr. Boris Todurov, in the video clip. “Now let’s turn on the generator – sorry, it will take a few minutes.”

The attacks also affected hospitals and clinics in southeastern Ukraine. The WHO said in a statement last week that it had confirmed at least 703 attacks between February 24, when Russian troops entered Ukraine, and November 23.

The Kremlin has denied allegations that it is targeting civilian targets. Kremlin spokesman Dmitry Peskov last week insisted once again that Russia only targets sites “directly or indirectly linked to military power.”

But just last week, as a result of an attack in the maternity ward of a hospital in eastern Ukraine, a newborn died and two doctors were seriously injured. In the north-east of the Kharkiv region, two people were killed as a result of shelling by Russian troops at a dispensary.

In Lviv, Duda said the explosions were so close to the hospital that “the walls were shaking” and doctors and patients had to go down to a basement shelter — something that happens every time an air raid siren sounds.

In the hospital, which specializes in the treatment of oncological diseases, only 10 of the 40 operations planned for that day were performed.

In the recently recaptured southern city of Kherson, deprived of electricity after the retreat of the Russians, paralyzed elevators are a real problem for paramedics.

They have to carry immobile patients up the stairs of residential buildings, and then lift them back to the operating rooms.

Throughout Kherson, where it gets dark after 4 p.m. at the end of November, doctors use headlamps, phone lights, and flashlights. In some hospitals, the main equipment no longer works.

Last Tuesday, Russian strikes on the southern city wounded 13-year-old Artur Voblikov, and doctors had to amputate his arm. Medical workers carried the teenager up the dark stairwells of the children’s hospital to the operating room on the sixth floor.

“The breathing machines are not working, the X-rays are not working. … There is only one portable ultrasound scanner, and we always carry it with us,” said Uladzimir Malishchuk, a doctor of surgery at the Children’s Hospital in Kherson.

The generator used at the children’s hospital broke down last week, leaving the facility without any electricity for several hours. Doctors wrap the newborns in blankets because there is no heat, said the deputy head of intensive care, Dr. Olga Pilarskaya.

The lack of heat makes operations on patients more difficult, said Dr. Maia Mendel of the same hospital. “No one is going to put a patient on the operating table in sub-zero temperatures,” she said.

Health Minister Viktar Lyashko said on Friday that there are no plans to close any hospital in the country, no matter how bad the situation is, but the authorities will “optimize the use of space and accumulate everything necessary in smaller areas” to provide heating. easier.

Lyashko said that all Ukrainian hospitals are equipped with diesel or gas generators, and in the coming weeks another 1,100 generators sent by the country’s Western allies will be delivered to hospitals. Now there is enough fuel in hospitals for seven days, the minister said.

Additional backup generators are still urgently needed, the minister added. “Generators are designed for short-term operation – three or four hours,” but the power outage can last up to three days, Lyashko said.

In the newly recaptured territories, the medical system is faltering after months of Russian occupation.

Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky accused Russian troops of closing medical facilities in the Kherson region and looting medical equipment – even ambulances, “literally everything.”

Dr. Olga Kobevka, who recently returned from the recaptured areas of Kherson after delivering humanitarian aid, repeated the president’s words in an interview.

“The Russians even stole towels, blankets, and dressing materials from the medustans,” Kobevko said.

In Kyiv, most hospitals are working as usual, but part of the time they are running on generators.

Meanwhile, smaller private practices and dental clinics are struggling to keep their doors open to patients.

Dr. Viktar Turakevich, a dentist from Kyiv, says that he has to postpone even urgent appointments because the power cut in his clinic lasts at least four hours a day, and the generator he ordered takes weeks to be delivered.

“Each doctor must answer the question of who he will take first,” Turakevich said.

Power outages also made it difficult to access patient records online, and the Health Ministry’s system that stores all data was unavailable, said Kobevka, who works in the western city of Chernivtsi.

Lviv surgeon Duda said that three doctors and several nurses from his hospital left to treat Ukrainian soldiers on the front line.

“The war has affected every doctor in Ukraine, be it in the west or the east, and the level of pain we face every day is hard to measure,” Duda said.

___

Karmanov and Litvinova reported from Tallinn, Estonia.

___

Follow AP’s coverage of the war in Ukraine at: https://apnews.com/hub/russia-ukraina