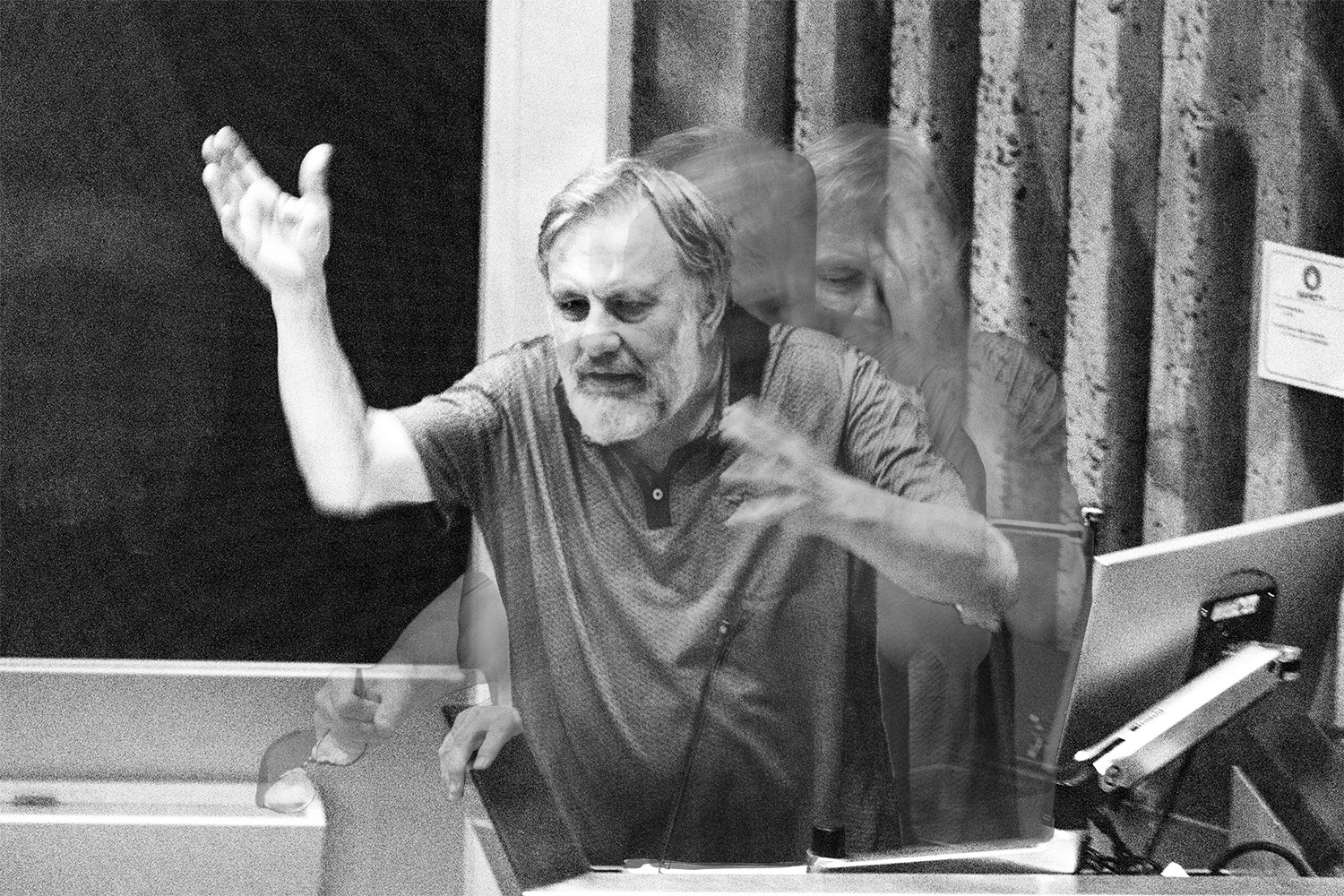

Seeing Slavoj Žižek perform in person is both entertaining and educational.

On November 3, the 73-year-old Slovenian philosopher and writer gave a wonderful speech at New York University’s Meyer Hall. – he interrupted himself and rummaged through his notes. He was in top form and his audience was, for the most part, enthralled.

On Thursday night, Žižek spoke to a typically young, generally enthusiastic audience of about 200 people. Most of the attendees had notebooks. One older visitor drew on the edges of a blank sheet of paper, nodding occasionally. He did not stay until the end.

Like a jazz musician who alternates between a set melody and long passages of virtuoso improvisation, Žižek briefly addressed the nominal theme of the event (interpretation current events as the four horsemen apocalypse) before returning to what he really wanted to talk about.

Žižek played all the hits, making his signature arguments around the works of thinkers such as H.W.F. Hegel, Karl Marx, Sigmund Freud and Jacques Lacan. He spoke more or less continuously during the two-hour event.

The incessant monologue was fueled by his trademark tics: sniffing, of course, as well as plucking his shirt, covering his eyes with both hands, flicking his tongue between the corners of his mouth, and saying phrases like “and so on.”

“It shouldn’t be underestimated the degree to which the great culture war today is a war to return — which you certainly can’t do — to the old patriarchal morality and so on,” Žižek said at an event hosted by New York University’s Department of Comparative Literature. . and a program of poetics and theory.

Žižek devoted time to discussing the ideological conditions in Russia, Ukraine and the United States – briefly touching on his homeland, which he fondly called “my shitty country, Slovenia” – but he emphasized the global nature of the struggle against what he called the new fundamentalism.

He said he identifies with the term “communist” to emphasize that global problems require a globally coordinated left-wing effort. Socialism, in Žižek’s opinion, doesn’t cut it, while anarchism hardly merits consideration. (Liberalism is not considered at all.) Global cooperation or global war are the two outcomes he foresees. “I’m more of a historical pessimist,” he said.

The fundamentalist ideology to which Žižek has dedicated his resistance doesn’t work without sex, he says, and the philosopher didn’t shy away from sex on Thursday night. A world in which even the most intimate acts are supplanted by technology has no shortage of funny but cringe-worthy anecdotes that Žižek enthusiastically told audiences: for example, two identical sex toys going at it on behalf of their owners, or a pornographic artist who himself demanded pornography to continue doing his job.

However, he did not always give such vulgar examples, even though he caused laughter in the crowd. He found echoes of the same principles in the written prayers that pray for you, the paid mourners that weep for you, the television show that laughs for you.

Among Žižek’s signature intellectual projects is Lacan’s promotion of Freudian psychoanalysis still having a place in the modern world, despite the modern impulse to treat superficial symptoms with medication or therapy. Psychoanalysis, according to Lacan and Žižek, really deserves developments that allow us to understand our deepest truths. “Only today is the time for psychoanalysis,” Žižek wrote in his book How to Read Lacan in 2006.

For the uninitiated in the audience, much of Žižek’s monologue borders on the incomprehensible. Devotees, however, laughed at the jokes to properly appreciate the profound things that require years of study.

But Žižek is not quite elitist. He expressed his delight at Don’t Worry, Darling (directed by Olivia Wilde), a 2022 film starring Florence Pugh, Harry Styles and Chris Pine, as part of a tangled argument that didn’t quite land, though he described it as “ the lowest of the lowest of my guilty pleasures.’

During the conversation, Žižek periodically joked with Avital Ronel, who was sitting in the first row. Ronell is a personal friend of Žižek, a leading scholar in psychoanalysis and deconstructivism and a professor at New York University. (Ronell was also suspended by the university for the 2018-19 academic year inappropriate verbal and physical contact to a graduate student she advised.)

Žižek interrupted himself at one point to ask Ronel how much he had left to say. (“Where am I, temporarily?” is his exact wording). “Four more hours,” she quipped. About half an hour remained, although Žižek would have used another hour and fifteen minutes.

(Alex Tay for WSNs)

Zhengzhi Jiang, a philosophy and film major at NYU, credits Žižek with leading him down what he calls “this disastrous path of philosophy.”

Although Jiang said that Lacan’s approaches, like Žižek’s, are not particularly popular in NYU’s philosophy department, he personally remains a fan of them. “No matter how overrated he is, he’s still probably one of the best philosophers in the world alive right now,” Jiang said.

“He’s the only successor to Lacan that exists in this world,” added Alyssa Lunn, a freshman at New York University studying computer science and game design.

Jan Szabo, a graduate student studying history at the New School for Social Research, said he has been engaged with Žižek’s ideas for some time. None of the topics covered Thursday night surprised him, but he enjoyed the show nonetheless.

“I expected more of the atmosphere of being around Žižek,” Szabo said. “I knew exactly what he was going to say before he said anything because he says the same thing every time.”

Žižek seemed to understand that this performance was what most of the audience expected. Several comparative literature students in attendance said they wished Žižek had more rigorously developed concepts such as revolutionary defeatism as they applied to topics such as the Russia-Ukraine war.

But when Slavoj Žižek shows up to give a speech, his memetic popularity precedes him. Žižek impressions have over 73 million views on TikTok. His catchphrase “I’d rather not” can be bought at mugs, posters and many t-shirts. This is not to mention the titanic return of his real intellectual work.

Given this pressure, enjoying a Žižek lecture requires a certain dedication.

“To understand Marxist theory, you must already be involved in it,” Žižek said at one point in the conversation. “It’s the same with love,” he added, and it’s the same with religion—once one understands it on an emotional level, rational arguments come easily.

But until this intuitive understanding is achieved, logic is unconvincing, even inaccessible. Žižek himself is a person, a philosopher, a performer – about the same.

Contact Alex Tay at [email protected]